Key Takeaways:

- As the world embraces the energy transition mining companies stand to be one of the primary winners.

- Clean energy requires considerably more metals than fossil fuel alternatives, meaning elements like copper, lithium, aluminium, nickel, zinc and rare earths are set to be in record demand.

- Companies that specialise in producing these elements – such as miners – are strongly positioned to benefit from the energy transition.

Introduction

As the world embraces clean energy the mining industry is set to be one of the biggest winners. Generating, transmitting and storing electricity from solar and wind power requires vast quantities of metal. Copper and aluminium are needed on a grand scale for expanding the grid. Nickel, cobalt and lithium are required to build millions of industrial batteries. If climate pledges are to be honoured, these metals must be mined on an order of magnitude greater than they are today.

While investors increasingly understand the investment opportunity the energy transition offers, few have focussed what it inevitably means for the mining industry. This article explains the opportunity, challenges, and potential risks of the next sectoral mining boom.

The Energy Transition Needs Metal

The energy sector is the world’s largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. According to numbers compiled by Oxford University’s Our World in Data, the energy sector accounts for roughly 73% of global greenhouse gasses. Within the energy sector, the largest sources of energy consumption are industry (24%), heating and lighting buildings (17.5%), and transport (16% of total).

If we are to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, then changing how we produce, store, and consume energy is crucial. Thermal power stations—gas turbine and coal fired—must be replaced with solar arrays, wind farms and nuclear power. Millions of industrial batteries must be built to store electricity. Boilers and gas heaters – which heat homes and buildings – must be replaced with electric alternatives instead. The world’s car fleet must go electric, a process that’s already underway. Hydrogen must be embraced to clean up areas – like shipping and ammonia production – that cannot be electrified.

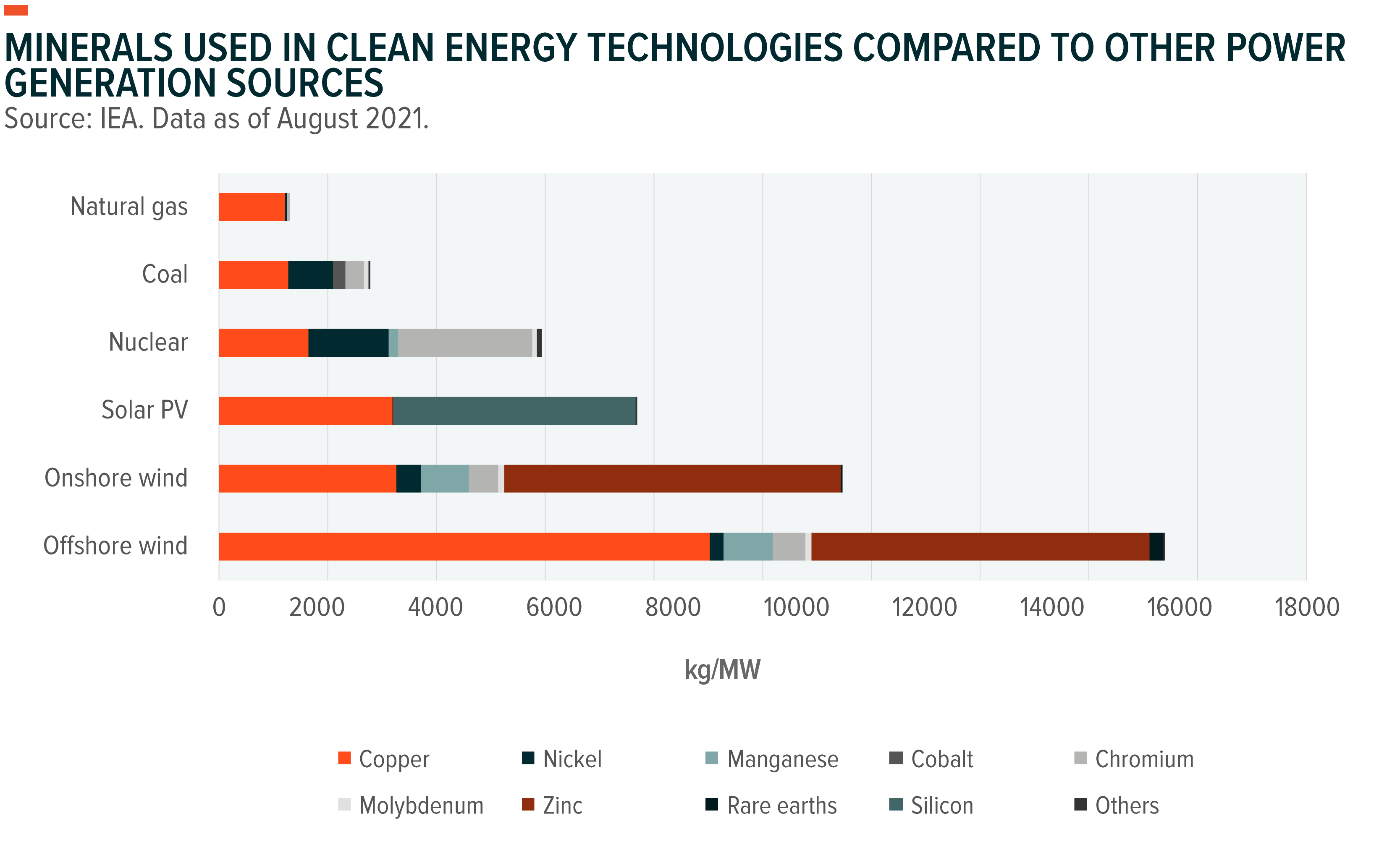

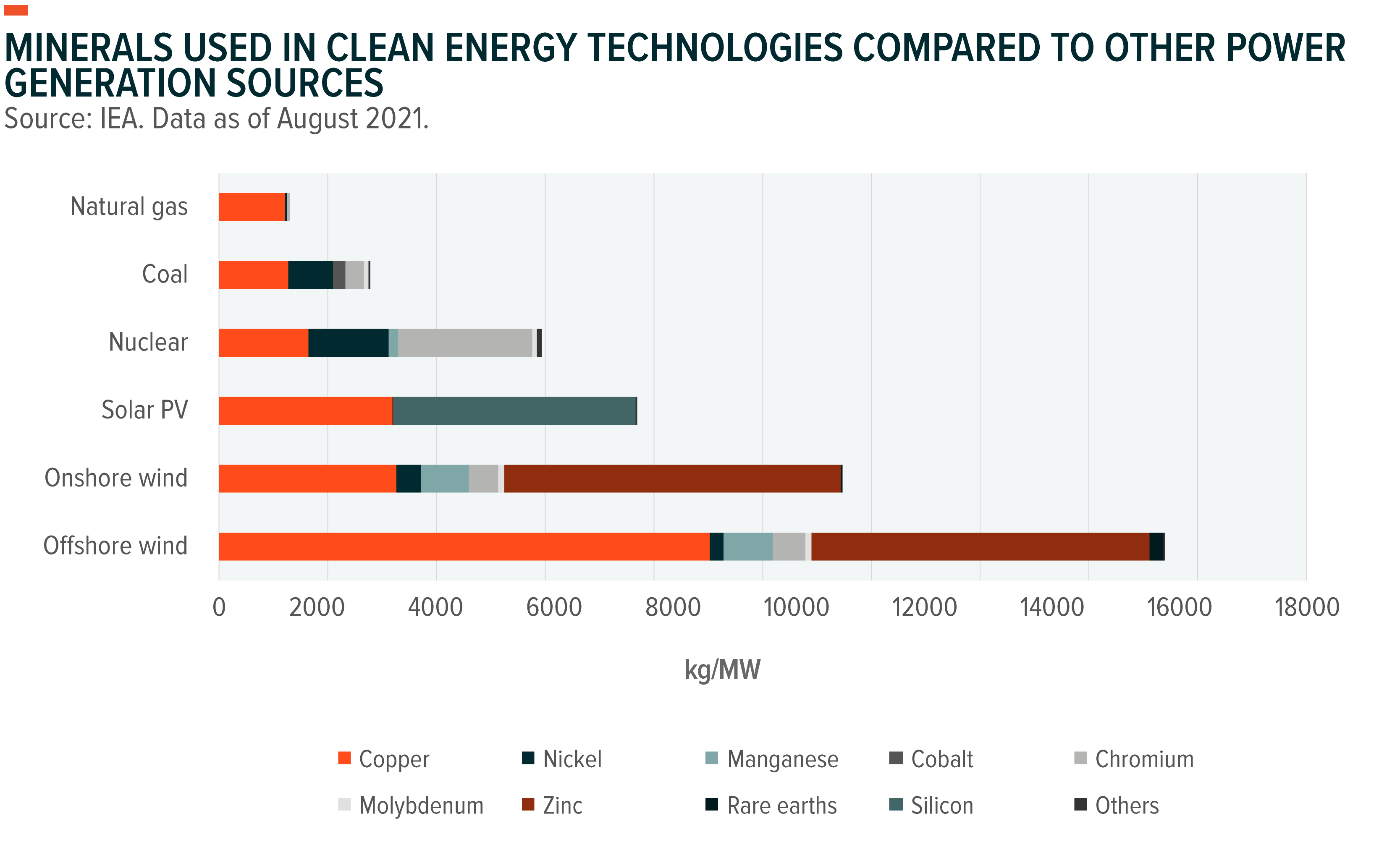

Achieving this paradigm shift will require enormous amounts of metal. Why? Because renewable energy requires much more metal to produce the same amount of power as fossil fuels. To give some examples, building a coal-fired power plant requires 1 – 1.5 tonnes of copper for every megawatt of electricity it produces. By contrast, an offshore wind farm requires 8 tonnes, and a solar array requires 2.8 tonnes to produce this amount of electricity.

Another example is cars. Making a conventional car requires 22 kilograms of copper. But making an electric car requires 53 kgs of copper, and many other metals as well, such as lithium and cobalt for the batteries, and rare earth elements – “rare” in the sense that they are rarely mined – for motors.

An in-depth study published by the International Energy Agency in 2021 tried to quantify exactly how much metal would be needed for the energy transition. The study’s results were quite startling. It found that if the Paris Agreements were to be met, then demand from clean energy technology for these metals would quadruple by 2040. And if the more ambitious net-zero by 2050 climate targets were to be met then demand would increase sixfold over this period.

Putting these numbers into context, the IEA found that while today, revenue from coal production is ten times larger than that from energy transition minerals, the combined revenues from these transition minerals could “overtake those from coal well before 2040.”

The energy transition therefore represents a significant opportunity for the mining industry, and one that is already unfolding

Is It Already Priced In?

Buying shares in energy transition metals miners is not a new concept to Australians. In recent years, shares of energy transition miners – especially lithium miners – have become popular with investors across the spectrum. This has meant that miners’ valuations reflect expectations of the energy transition already.

We can see this if we look locally at the ASX. The valuations of coal miners like Whitehaven Coal have compressed (partly thanks to the rising coal price, due to the Russia-Ukraine war), while the valuations of pureplay lithium miners like Pilbara Minerals have expanded. This reflects the forecasted shift in revenues away from coal miners and towards energy transition metals miners, as shown in the chart above. (Many lithium miners have enjoyed an additional bump this year thanks to ASX 200 index inclusion). This raises questions about whether the energy transition is already fully priced.

Source: Bloomberg, 19 October 2022

In Global X’s view, energy transition metals miners will likely trade on higher valuations for the foreseeable future. Markets are forward looking, and due to the sheer scale of demand for these metals in coming years and the relative lack of supply, these miners’ share prices will likely trade at a premium. Potentially supporting these higher valuations is the growth of ESG mandates, which are bifurcating the mining industry. We review each of these in turn below.

The Supply Deficit

As production of low carbon technologies increases, energy transition metals are almost universally forecast to face a supply shortage.1 The reason being, that while demand is set to grow exponentially, it is unlikely that supply can grow fast enough to catch up.

Why will supply fall short? Because building new mines is risky, very slow and is often done by companies with limited capital compared to the development funding required. Exploration, where prospectors scout the globe in search of deposits, is lottery-like in its chance of success, with only one in one thousand geological concepts resulting in a new producing mine. Once deposits are found, getting a new mine approved by governments can take many years, given the environmental and community disruption that is often involved. Building a new mine is then obstructively expensive. It requires employing hundreds of staff, buying specialised machinery, and building infrastructure as mines are often in remote areas. Once built, mines do not typically breakeven until after several years of production.2

Taking copper as an example, it usually takes 4-12 years to open a copper mine, and it can cost over $1 billion, depending on the type of mine.3 Lithium mines, as another example, take at least five years to open4 and typically costs more than $100 million. On average it takes 16 years from discovery to open a new producing mine, depending on the metal in question.

There is a consensus among analysts that these production times are set to lengthen. Reasons for this include the fact that enrolments in mining engineering and metallurgy have fallen globally creating a worker shortage.5 Under public pressure to protect the environment, global governments have made mining permits harder to get. Meanwhile, mining executives’ incentives focus on short-term returns, not returns in 10 years’ time.6

Estimates differ over the size of the looming supply crunch. The IEA believes that if climate goals are to be met, then supply from existing mines and those under construction provides “only half of projected lithium and cobalt requirements and 80% of copper needs by 2030. Today’s supply and investment plans are geared to a world of more gradual, insufficient action on climate change… They are not ready to support accelerated energy transitions.”7 Morgan Stanley also forecasts lithium supply deficits, but of a more modest size. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence expect the deficit to expand exponentially.

While disagreement exists over the size of the deficits, there is consensus that supply shortages are relatively certain for the medium to long term. This supply/demand imbalance has meant that lithium miners like Pilbara and Allkem were enjoying gross margins over 75% in FY2022, prompting Elon Musk to compare them to the software industry.8 For bauxite (aluminium) and copper miners in early 2022, cash margins were in the highest 90th percentile, due to record aluminium and copper prices. These fundamentals naturally mean that green metals miners have commanded premium valuations.

The Growth of ESG Mandates

Providing further support for energy transition metals miners could be ESG investment mandates. Under pressure from end-clients, institutional investors like superfunds are increasingly divesting from fossil fuel companies. This implicates many diversified miners, which are often involved in coal, oil or gas.

These mandates are significant because institutional investors’ buying power means they are influential in determining share prices. One study has found fossil fuel divestment by institutional investors is already placing downward pressure on fossil fuel companies’ share prices.9

As these mandates become more common, we believe the mining sector could be impacted. Importantly, we can see those miners that avoid fossil fuel extraction and focus on energy transition metals benefitting, as institutional investors buy their shares in larger quantities. While fossil fuel miners suffer for the same reason.

Conclusion – Rediscovering The Resources Sector

Global X believes that Australian investors have fallen out of love with the resources sector the past 10 years. Driven by lower commodities prices and growing disaffection with coal mining, many local investors have sought opportunity elsewhere. However with the energy transition driving a surge in green metals prices, investors are rediscovering the sector once more.